Software architecture is hard. Creating a simple, consistent, flexible environment in which we can solve the customer’s ever-changing problems is no easy task. Keeping it that way is harder still. Striking the right balance between all the competing demands takes real skill – so what does it take to create a good architecture? How much architecture is enough?

Software Architecture

First, I’m drawing a distinction between software architecture and enterprise architecture. By software architecture I mean the largest patterns and structures in the code you write – the highest level of design detail. I do not mean what is often called enterprise architecture: what messaging middleware to use, how are services clustered, what database platforms to support. Software architecture is the stuff we write that forms the building blocks of our solution.

The Over Architect

I’m sure we’ve all worked with him: the guy who could over think hello world. When faced with a customer requirement his immediate response is:

we need to build a framework

Obviously the customer’s problem is too simple for this genius. Instead, we can solve this whole class of problems. Once we’ve built the framework, we just need to plug the right values into the simple 400 line XML configuration file and hey presto! customer problem solved.

Obviously the customer’s problem is too simple for this genius. Instead, we can solve this whole class of problems. Once we’ve built the framework, we just need to plug the right values into the simple 400 line XML configuration file and hey presto! customer problem solved.

Sure, we’ve only been asked to do a one-time CSV import of some customer data. But think of the long-term, what will they ask for next? What about the next customer? We should write a generic data import framework that could take data in CSV, XML or JSON; communicating over HTTP, FTP or email. We can build rich, configurable validation logic. We can write the data to any number of database platforms using a variety of standard ORM frameworks. Man, this is awesome, we could be busy for months with this!

Whatever. You Ain’t Gonna Need It!

But sometimes, the lure of solving a problem where you’re the customer, is much more intellectually stimulating than solving the boring old customer’s problems. You know, the guy who’s paying the bills.

The Over Architect generalises from a sample size of one. Every problem is an opportunity to build a more general solution, despite having no evidence for what other cases might need to be solved. Every problem is an opportunity to bring in the latest and greatest technology – whether or not its a good fit, whether or not the company’s going to be left supporting some byzantine third party library that’s over kill for their simple use. An architect fully versed in CV++

The Under Architect

On the other hand, the Under Architect looks at every customer problem and thinks:

we could re-use what we did for feature X

Where by “re-use” he means copy & paste, change as necessary. There’s no real architecture, just patterns repeated ad infinitum. Every new requirement is an opportunity to write more, new code. Heaven forbid we go back and change any of that crufty old shit. No, we’ll just build shiny, brand new legacy code.

Where by “re-use” he means copy & paste, change as necessary. There’s no real architecture, just patterns repeated ad infinitum. Every new requirement is an opportunity to write more, new code. Heaven forbid we go back and change any of that crufty old shit. No, we’ll just build shiny, brand new legacy code.

We’re building a web application: so we’ll need some Controllers, some Views and some Models. There we go, MVC – that counts as an architecture, right? Oh, we need a bit more. Well, we’ve got some DAOs here for interacting with the database. And the business logic? Well, the stuff that’s not wrapped up in the controllers we can put in FooManager classes. Sure, these things look like monolithic god classes – but its the best way to aggregate all the related functionality together.

Lather, rinse, repeat and before you know it you have a massive application with minimal structure. The trouble is, these patterns become self-perpetuating. It’s hard to start pulling out an architecture when all you have is a naming convention.

The Many Architects

The challenge in many software teams is everyone thinks it’s their job to come up with new architecture or start building a new framework. The code ends up littered with half-finished, half-forgotten frameworks. Changing anything becomes a nightmare: was all this functionality used? We have three different ways of importing data, via three different hand-rolled frameworks – which ones are used? How much of each one is used? Can I refactor them down into one? Two? What about the incompatibilities and subtle differences?

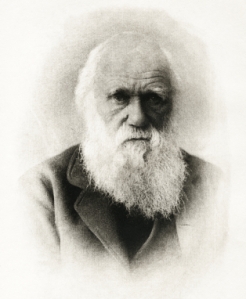

Without a clear vision changing the code becomes like archeology. As you delve down through the layers you uncover increasingly crufty old code that nobody dares touch any more. It becomes less of a software architecture and more of a taxonomy problem – like Darwin trying to identify a million different species by their class structure.

Without a clear vision changing the code becomes like archeology. As you delve down through the layers you uncover increasingly crufty old code that nobody dares touch any more. It becomes less of a software architecture and more of a taxonomy problem – like Darwin trying to identify a million different species by their class structure.

The Answer

What’s the answer? Well I’m sorry, but I just don’t buy this agile bullshit about “emergent architecture”. Architecture doesn’t emerge, it has to be imposed, often onto unwilling code.

Architecture requires a vision: somebody needs to have a clear idea about where the software is headed. Architecture needs patience: as we learn more about the problem and the solution, the architecture will have to adapt. Architecture needs consistency: if the guy calling the shots changes every year or two, you’ll be back to the Many Architects problem.

Above all, I think good architecture needs a dictator. Some, single person – taking responsibility for the architecture. They don’t need to be right, they just need to have a clear vision of where the architecture should head. If the team are on board with that vision then the whole team are pulling in the same direction, guided by one individual taking the long view.

Central Architecture Group

This sounds like I’m advocating a central architecture group? Hell no. The architect needs to be involved in the code, hands-on, day-to-day, so he can see the consequences of his decisions. He needs the feedback from how the product evolves and how our understanding of the problem evolves. The last thing you need is a group of ivory tower architects pontificating about whether an Enterprise Service Bus is going to solve all our problems. Hint: it won’t, but firing the central architecture group might.

Conclusion

Getting software architecture right is a hard problem. If you keep your code DRY and SOLID, you’re heading in the right direction. If someone has the vision for where the code should head and the team work towards that, relentlessly cleaning up old code – then maybe, just maybe you’ve got a chance.

Nice summary of how architecture can go wrong and some good ingredients on how to make it go right. From your post, I think you’d enjoy my book, Just Enough Software Architecture. I’d be happy to send you a copy.

Regards,

-George

Hi Dave,

I like this post. It reminds me when some project managers favor the methodology over the project’s success (see this post.

You are into something when you say that “architecture needs a dictator” although I’m sure “dictator” is not the word people want to hear. Let me try to rephrase it, hopefully without changing the idea. If I did, please correct me.

I think we can more or less agree that architecture imposes constraints on software development, above and beyond customer requirements. Sometimes customers care about technical details, sometimes they don’t. In any case, technical constraints handed down by customers are first and foremost requirements, leaving us little choice, but to meet them.

Typically constraints not imposed by customers cause controversy. Here we have real alternatives. If somebody, let’s call him an architect/designer, wants to impose additional technical constraints, we are right to question what justification he has for doing it.

In many cases, such justifications exist. It is just hard to talk about them, because they vary tremendously. When strong, objective reasons exist why we should do things in a certain way I like to call them “design requirements”. Customers don’t care, but we do because it would be unwise to ignore them.

Say that for some very good reasons we conclude that we need to break our software into two modules, A and B. Once we made this decision, whole set of new technical constraints result for A and B, otherwise they would never work together. It is typically the architect’s job to spell out what these constraints are. It is fair to claim that if breaking the software into A and B made sense in some big scheme of things, all technical constraints resulting from this decision should be also accepted.

And this is where things start to get messy. Developers rarely question the high-level design requirement, but love to push pack against specific technical constraints, because, well, nobody likes constraints. Since there is no single, obvious way of turning design requirements into a set of constraints, unless the architect/designer is trusted to do this using his best judgment, there is fertile ground here for all kinds of unproductive debates.

In conclusion, it is not as much that the architect/designer is accepted as a dictator, rather than he is trusted to do his job. Whether this is essentially the same thing, I’ll let you decide.

Great point. And absolutely right, an architect trying to lead by force of management will won’t get very far. As you say, the architect needs to be trusted.

The only reason I use the word dictator is that sometimes you just have to go with what the architect says. We could do A, we could do B. There are pros and cons and no obvious way of choosing. It’s the architect’s job to make that call, even if some developers disagree with it. Often there won’t be an obvious reason to choose one way or another – this is where having a single voice, I believe, is critical.

Regarding constraints, there are (at least) two interesting kinds. The first is a kind of requirement that the sw team has no control over, like it must run on Sun hardware, or it must be completed by January. The second kind is one that the team imposes on itself deliberately.

I call the latter “guiderails” because their purpose is to point the project in a deliberate direction, technically. For example, on my current project, the biggest risk at the beginning is that we couldn’t handle the data volumes within our SLA (a couple hours). So we used a map-reduce architecture that comes with a ton of constraints on how we must program. But these are not capricious; they are there to ensure the computations are parallelizable across hardware.

And let me tell you those constraints (guiderails) are a pain — but it would be worse if the app didn’t scale horizontally. We currently have 15 machines with 8 cores and 16 drives each and that’s just barely enough. Good thing the client knows they can simply buy hardware to speed things up, which we had to do in development to support several Hudson continuous integration builds. Another team around here didn’t impose such guiderails and they’re hitting the wall on their current hardware, forcing a redesign.

When architecture is done right, it’s largely about understanding what the system has to do beyond its functional requirements and judiciously installing guiderails so that those quality attributes can be achieved.

At the risk of sounding like an advertisement, this is discussed more in my book and several chapters are available free online (http://rhinoresearch.com/book).

-George

You say that you don’t buy into “emergent architecture”. Yet, three sentences later you say “Architecture needs patience: as we learn more about the problem and the solution, the architecture will have to adapt.” Hmmm.

Hehe damn – good point.

I guess what I mean is that I don’t buy that good architecture will just magically happen. Obviously the architecture needs to evolve to suit the problem domain, but that progress needs to be guided with a vision – otherwise you get lots of competing ideas and an incoherent architecture.

Otherwise a very good post btw.

Nice post. I largely think the same way.

Architects, or better: people who call themselves architects, go through several stages of ignorance and stupidity. That is a lifelong process, I think.

I find parallels to the Dreyfus Model of Skill Acquisition quite helpful. I found the following presentations very illustrative:

http://www.infoq.com/presentations/Developing-Expertise-Dave-Thomas

http://www.infoq.com/presentations/Sharpening-the-Tools

From my experience, software architecture actually does emerge when you apply a handful of principles (you named DRY and SOLID) to every detail and every piece of code. Sure, with more experience you will start from a point with more likelihood for success, but still, as you proceed, the “always true” principles need to be applied to shape the architecture.

Over the years I came to think there are a kind of natural laws for programming and similar to the basic forces in physics, they become more abstract and comprehensive with time and less numerous.

If you have a vision, it also must be constantly measured against those laws to check if you are on the right track.

A German chancellor once said “When you have visions, visit a doctor” :-). Just kidding.

– Hermann