In most sensible languages the compiler ignores whitespace; it’s only there to help humans understand the code. The trouble is, without automated checking of whitespace it’s very hard to have consistent style. Without a compiler telling you when you get it wrong, it’s hard to enforce a standard. Sometimes it leads to bugs and, ironically, hard-to-understand code. Maybe it’s time to realise that formatting of code is different from its semantics. Maybe in the 21st century, programmers should be using more than just a text editor?

No Whitespace

For example, the following is perfectly legal Java:

public String shareWishList() {

User user = sessionProcessor.getUser(); WishList wishList =

loadWishList.forUserByName(user, selectedWishListName); for(

String friend : friends) { if ( !friend.equals("") ) { new

ShareWishListMail( friend, user, wishList, emailFactory,

this.serverHostName ) . send(); } } return "success";

}

But most normal human beings would much prefer to see this written the “traditional” way, with line breaks in appropriate places and sensible use of the space character:

public String shareWishList() {

User user = sessionProcessor.getUser();

WishList wishList = loadWishList.forUserByName(user,

selectedWishListName);

for (String friend : friends) {

if (!friend.equals("") ) {

new ShareWishListMail(friend, user, wishList,

emailFactory,

this.serverHostName)

.send();

}

}

return "success";

}

Builders

Of course, most IDEs can reformat code for you. And with careful tweaking of the settings you can get something useful. But there are always cases where you want to do something different, to help readability.

For example, I often format uses of builders differently to other code. While I might normally prefer long lines to be wrapped and continue to the line break on the following line, when calling a builder it makes it hard to read:

Trade trade = tradeBuilder.addFund(theFund).addAsset(someAsset).atSharePrice(2)

.forShareCount(10).withAmount(20).tradingOn(someDate)

.effectiveOn(someOtherDate)

.withComment("This is a test trade").forUser(myUser)

.withStatus(ACTIVE).build();

This is about a billion times easier to read as:

Trade trade =

tradeBuilder.addFund(theFund)

.addAsset(someAsset)

.atSharePrice(2)

.forShareCount(10)

.withAmount(20)

.tradingOn(someDate)

.effectiveOn(someOtherDate)

.withComment("This is a test trade")

.forUser(myUser)

.withStatus(ACTIVE)

.build();

Test Setup

Tests seem to end up particularly dependent on whitespace. For example, in my current job I recently had cause to try and write something like the following:

var sharePosition = CreateAnnualSharePosition

.InAsset(someAsset)

.Quarter1Shares(0) .WithQ1Price(1.250, GBP)

.Quarter2Shares(10000) .WithQ2Price(1.15, GBP)

.Quarter3Shares(1000000) .WithQ3Price(1.35, GBP)

.Quarter4Shares(1000000) .WithQ4Price(1.45, GBP)

.Build();

Because I had several similar tests, with subtle variations of share count & price quarter-to-quarter it massively helped me while writing it, to have it clearly laid out – so I could see when share count had changed and when price had changed. Unfortunately, VisualStudio had other ideas and removed some of my whitespace when copy & pasting this, which led to me reformatting every damned time.

Internal DSL

Effectively these builders are a form of internal DSL. You’re (ab)using the source language to provide a domain specific language to let you describe what you want to actually do. My previous company used a home grown Java based BDD framework – Narrative. This leads to very fluent acceptance tests, but lots of method chaining. As with the builder pattern this would be totally unreadable without liberal use of whitespace. Take this not particularly unusual example:

Then.the(user)

.expects_that(the_orders(),

Contains.only

(an_order()

.of_type(SELL)

.for_asset(someAsset)

.for_amount(150, gbp())

.with_trades(

allOf(

Contains.inAnyOrder(

a_trade_selling("Sub asset 1"),

a_trade_selling("Sub asset 2")),

trades_totalling("150")

))));

Now, there’s a very particular “style” to how this is laid out. Whoever thought this looked clean and readable (probably me) was clearly on something that day. But it’s difficult to lay out a “sentence” like this because of the massive amount of nesting inherent in what it’s saying.

How can we possibly define rules for whitespace to layout such statements in a clear, readable, machine-enforceable way? After months of seeing different people spend endless hours tweaking whitespace to their own personal preference you know what I realise? You can’t automate it.

So maybe we’re trying to solve the wrong problem? Is the fact that we’re so reliant on whitespace to make code not look like total shit, a hint that maybe our text editor isn’t giving us the expressive power we need? Maybe, just maybe, in the 21st century, programmers could be using something richer than a text editor? Maybe there’s some structure in our source code that we could show better?

Builders – Revisited

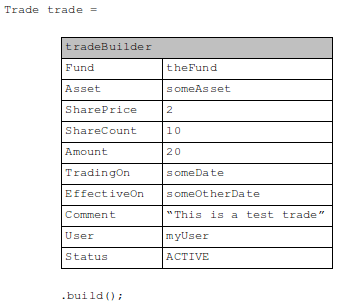

Let’s go back to a simple example, my trade builder. Wouldn’t this be easier to read if it was written in the table it so obviously is?

Shock! Horror! Fancy that! Source code that’s not just plain old text but – OMG – a table. The humanity of it! Sacrilege! Giving programmers powerful, expressive, rich text instead of a dumb old text editor.

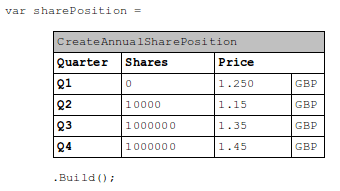

My share position builder is helped even more by being expressed in a table:

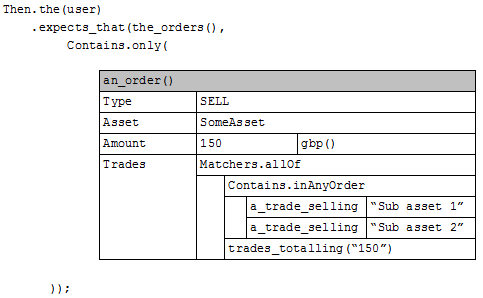

But what about the complex set of nested matchers?

Here the nested structure is clearly visible, there’s no need to rely on whitespace – the nested structure is clear and unambiguous. The editor understands the structure and renders the correct layout making it easy to write and much easier to read. It actually becomes impossible to indent things wrong accidentally: a nested table is either nested or it isn’t.

But… how would it work?

Well, obviously our editors would need to be more powerful to support this. The indentation can be derived from the source code: the editor can parse brackets much more easily than the human eye and translate that to a more structured form that’s easier to read.

The critical part is defining the presentation style when declaring a method/class – e.g. identifying builder methods so we can present more naturally.

Would it work?

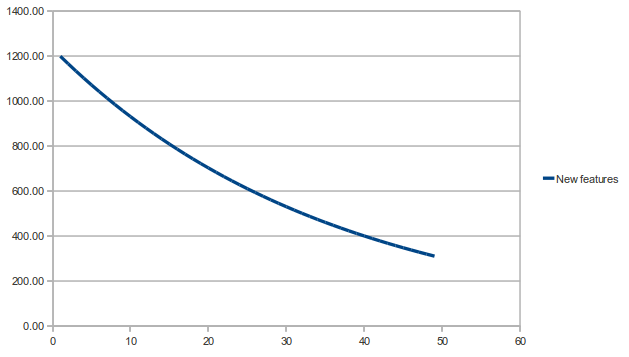

There are numerous implementation details – but I’m sure it could be made to work easily enough. But, is the complexity worth it? Am I stark raving mad or is it about time our editors were dragged kicking and screaming into the 20th century?